By Bailey Shoemaker Richards

Move over Mother’s Day – there’s a new holiday in town, and it lasts a whole week. That’s right, yet another manufactured holiday has reared its head, looming over the cultural landscape for 7 straight days of non-stop princess marketing (not that there’s really ever a time without it, now it just gets to pretend it’s a holiday).

Move over Mother’s Day – there’s a new holiday in town, and it lasts a whole week. That’s right, yet another manufactured holiday has reared its head, looming over the cultural landscape for 7 straight days of non-stop princess marketing (not that there’s really ever a time without it, now it just gets to pretend it’s a holiday).

Cooked up by Disney and Target, Princess Week is a week designed to “celebrate the sparkle and wonder of every princess.” It’s an event for girls that encourages them to “celebrate their individuality” by purchasing identical manufactured toys and costumes of already heavily marketed princesses.

Disney alone has over 26,000 princess products on the market, in what has become a $4 billion dollar industry annually. And now this juggernaut of a marketing scheme has decided it needs to have a holiday. Consumerist packaging of conformity in behavior, dress and appearance, and limiting ideals of normalized white girlhood placed in almost identical stories of princesses becoming princesses and/or getting married – sounds like a holiday to me!

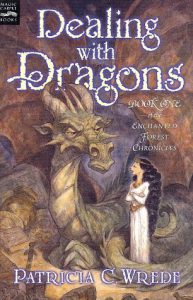

As I sat stewing over this latest marketing monstrosity, I picked up one of the books I’ve been rereading lately. The nostalgia bug bites everyone at some point, and it got me when I was browsing my bookshelves for something familiar to read. I went from Dealing with Dragons to Ella Enchanted to the Alanna series in quick succession, and realized that these stories were brimming with feminist messages. I missed the obvious implications as a young reader, but I have no doubt that these – some of my favorite and much dog-eared books – played a role in turning me into the feminist I am today.

So if Princess Week is going to become another cultural staple, I want to counter Disney’s vision of femininity and princesses with some of the women and girls from these books. In a world where Disney has almost 30,000 princess products that all send basically the same message about what it means to be a girl, some alternatives can only be a good thing.

Over at Princess Free Zone and Hardy Girls, Healthy Women, there’s been a lot of discussion about expanding the definition of girly, and by extension expanding what it means for a girl to celebrate Princess Week. These three books are an amazing place to start looking at some alternate definitions of what it means to be girly, and what it means to be a princess. The main characters in these books are, become or interact with princesses, and all of them have to deal with the implications of femininity in their own worlds.

Ella Enchanted is Gail Carson Levine’s take on the Cinderella story. In this version, Ella is literally incapable of disobeying a direct order, thanks to the “gift” of a bungling fairy godmother. The strict social rules of Ella’s world, from her curse to her wicked stepsisters to the finishing school she attends, make her life a constant challenge. Ella, however, manages to retain her spirit and uses all the ingenuity she possesses to circumvent her curse whenever possible.

Ella Enchanted is Gail Carson Levine’s take on the Cinderella story. In this version, Ella is literally incapable of disobeying a direct order, thanks to the “gift” of a bungling fairy godmother. The strict social rules of Ella’s world, from her curse to her wicked stepsisters to the finishing school she attends, make her life a constant challenge. Ella, however, manages to retain her spirit and uses all the ingenuity she possesses to circumvent her curse whenever possible.

As the story develops and Ella meets her prince charming, she begins to realize that as long as she has to comply with orders, and as long as the social rules of her world have a stranglehold on her agency, she cannot consent to marriage. It is only in defying the order she most wants to obey that Ella finds freedom. The metaphor for girls growing up in a modern society where advertisements, magazines and peer pressure constantly try to force us to conform to very specific behaviors is impossible to miss. Ella’s example of overcoming this pressure and staying true to herself while learning to navigate the challenging situations she encounters is hugely inspiring for young women struggling with peer pressure.

Cimorene, the protagonist of Dealing with Dragons (and three other books in the series), is the only one of these characters who starts out as a princess, and yet she defies the princess stereotype in some of the biggest ways. Toward the beginning of the book, Cimorene has an argument with her father, the king, about whether or not fencing, cooking and magic lessons are appropriate for a princess. Her father insists that these activities are ‘just not done’ by princesses. Cimorene counters that notion by asserting that she is a princess, and therefore they are done by princesses.

Cimorene, the protagonist of Dealing with Dragons (and three other books in the series), is the only one of these characters who starts out as a princess, and yet she defies the princess stereotype in some of the biggest ways. Toward the beginning of the book, Cimorene has an argument with her father, the king, about whether or not fencing, cooking and magic lessons are appropriate for a princess. Her father insists that these activities are ‘just not done’ by princesses. Cimorene counters that notion by asserting that she is a princess, and therefore they are done by princesses.

This way of expanding the definition of what is acceptable “princess” behavior also applies to girls who love dinosaurs and mud pies, but can also wear a tiara with the best of them – when they feel like it. Defining “girly” not as “all that is pink and frilly” but instead as “things that girls like to do” is a simple way to make activities inclusive and safe for girls to participate in.

Cimorene, to escape an arranged marriage, negotiates a job with a dragon. She agrees to become a dragon’s captive princess and organize the library and caves in exchange for not having to conform to traditional princess behavior. This unconventional arrangement attracts a lot of attention, and Cimorene ends up foiling a plot to take over the dragons’ court by the end of the first book.

And Alanna, the main character in The Song of the Lioness quartet, is a young woman who wants to be a warrior maiden – the first woman knight in a century. However, because the last woman knight died a century ago, girls are no longer allowed to train as knights. To get around this, Alanna and her twin brother Thom trade places: He leaves for a convent to study magic, and Alanna cuts her hair off and renames herself Alan, so that she can train to become a knight.

And Alanna, the main character in The Song of the Lioness quartet, is a young woman who wants to be a warrior maiden – the first woman knight in a century. However, because the last woman knight died a century ago, girls are no longer allowed to train as knights. To get around this, Alanna and her twin brother Thom trade places: He leaves for a convent to study magic, and Alanna cuts her hair off and renames herself Alan, so that she can train to become a knight.

Alanna’s transformation is one of the most dramatic – for eight years, she has to hide her gender from those closest to her (although some of them do discover her secret before that time is up). However, Alanna’s decision to hide her gender also causes her to question assumptions about what it means to be a girl, and eventually a woman. Although Alanna takes on the disguise of Alan, she struggles with wanting to express her femininity as she grows up, and constantly questions her friends on their penchant to dismiss weakness as something “girly.”

For Alanna, finding a balance between taking on a role and a career explicitly reserved for men, and retaining her sense of self as a woman, is something that many girls and women struggle with. Femininity is still derided as something weak, and women who want to engage in math and science-based careers often find that they must discard femininity if they want to be taken seriously. The struggle to balance authentic expression without being seen as frivolous is a theme throughout Alanna’s story.

Each of these books also offers their protagonist a chance to confront their own prejudices throughout the course of the books. Cimorene is not immune to gender stereotypes, despite her rejection of a confining definition of what it means to be a princess: she is startled to learn that the King of the Dragons is not always a male dragon (and at the beginning of the novel, there is a dragon who indicates that it has not even decided what gender it wants to be). Alanna must confront her class prejudice when she, a noble, receives a wedding proposal from a commoner. Ella must constantly reevaluate her relationships to friends and family throughout the book, and learn to overcome anger and disempowerment.

Young adult and middle grade literature often gets a bad rap for being too easy, too romantic or not serious enough for adult consideration, and yet a return to books I devoured as a child has revealed layers of thought and metaphor that were lost on me then. Any girl who feels left out by “Princess Week” or the over saturation of a very specific type of princess narrative – or who loves the Disney princesses but is curious about who else is out there – would benefit from picking up any of these books. Expanding the definition of what it means to be a girly princess is one of the best things we can do when the market is trying to tell girls there is only one way to do it.

I like this list, good suggestions. However, as a child I always was drawn to books where the women in the stories didn’t *have* to fight against “the system” (whatever it may be) in order to be powerful, either socially or magically. Books where it was simply a given that women could and did use magic, fight monsters, have adventures, etc etc. I am always glad for more women protagonists in YA Fantasy (or, you know, in literature in general) but the idea that we transplant a very real gender struggle from our world into theirs still, in some ways, is limiting. Even in escapist fantasy, I have to fight to be equal.

One of my favorite series as a young adult was Garth Nix’ Abhorsen series. In it, Sabriel, the main character, is the inheritor of a great magical legacy and it is a non-issue that she is female because magic is inherited regardless of sex. She proceeds to rescue a prince, slay a monster, and go on to have many other adventures with only a few passing mentions of her femininity being involved. Later in the series, her son and presumably her heir has to come to grips with the fact that he is incredibly ill-suited for his magical legacy, but is afraid to tell his mother the truth. Magic, in this case, is about lineage, not gender or even worth. The characters are complex and grow throughout each book, each seeking their own identity and searching for purpose. And I can’t think of any mention of, “But you’re a GIRL, you can’t… [XYZ]!” in it.

Sometimes, we get tired of having to fight in reality and want our escapist lit to be a reflection of the world we want to escape to. Even in fantasy, hearing or implying “Even though I am a girl, I can…” gets tiring, too. Women don’t have to go off and be “like men” to be successful, earn respect, etc. Sort of reminds me of the “backwards but in high heels” comment—what if you just… turned around, and danced by yourself? Know what I mean? A self-rescuing princess, so to speak. 🙂

When I met Tamora Pierce at a book signing, I thanked her for giving us Alannas in a market full of Bella Swanns. Thank you so much for including her Song of the Lioness series in your article! Ms. Pierce writes amazing fantasy chock full of strong female characters; it’s about time she got some recognition. 🙂

[…] response to Disney Princess week, Bailey Shoemaker Richards at SPARK counters with her own list of awesome princesses from MG/YA literature. As Bailey says: “The main characters in these books are, become or interact with princesses, […]

I have to take issue with the idea that Disney has only ever portrayed women negatively. Perhaps I’m sugar-coating the past: I am, after all, a child of the 90s, and so naturally, I have always adored Disney.

I’m well aware of the fact that Disney has always been a capitalist, consumerist American organisation, and of all the problems that come with this. Yet within the films, you almost always find authority figures and conventional ideologies being challenged. Mostly, the stories have been about sticking up for the underdog. True also, that Disney princesses nearly always get married and live happily ever after with their princes, and perhaps too much emphasis is placed on their pretty dresses (though I’m not sure there’s anything fundamentally wrong with dressing up if you want to). Early Disney films (Snow White, for an obvious example) certainly had some really dodgy sexual politics going on. However, the best thing about the films that I grew up on was that the heroines had evolved beyond these early dormant beauties. They’d woken up to the late twentieth century, and were far from just passive, hopeless, girly-girls. In fact, they’re not even all princesses.

I’ll give you a quick cut-down of what I took away from them. Ariel disobeys her father and runs away from home to satisfy her own curiosity. Belle (my favourite) is super-clever, loves reading, is a ‘funny girl’ who ‘doesn’t quite fit in’, rejects an arrogant proposal from manly-man Gaston, demands ‘adventure in the big wide somewhere’, and is brave enough to take her father’s place in the beast’s castle. Princess Jasmine refuses all her stupid suitors, sneaks out at night dressed as a commoner, and finally persuades the Sultan to change the law so she can marry who she wants to. Pocahontas is a pacifist and moves boldly between the two sides of the battle between Native Americans and European colonists – and she doesn’t even go off with John Smith, in the end. Esmeralda is an outlaw, hiding criminals, disgraced and despised by the establishment, and even directly challenges God at one point. Meg and the gospel choir in Hercules are fabulous, loud, powerful women. Mulan actually proves that she can easily out-man all the men! More often than not, it’s the silly girly types that get ridiculed (check out Ariel’s sisters or Gaston’s identical blonde admirers in Beauty and the Beast). But don’t take my word for it: rewatch them and see.

Yet, I’m just as horrified as you by the idea of ‘National Princess Week’. I like dressing up and doing silly things, but this feels beyond the pale, hideously cynical, consumerist and sexist. So what happened? As I see it, this whole princess week thing goes against the grain of what Disney films always taught me, which is that princesses are pretty much always trying NOT to be princessy, bidding for freedom from the social conventions that oppress them. As I’ve got older, I’ve felt increasingly irritated by what the franchise has been turning into. Disney is losing its magic, and I’m pretty sure that that’s not just me growing up, that they’ve undergone some fundamental shift in outlook. Well before this business, I’d noticed things going downhill. Going to the Disney Store, for example, used to be a real treat. Now it’s awful. They’ve all downsized, they all sell the same limited range of over-priced, poor quality tat, and all have average to poor customer service. In terms of films, too, more and more shoddy, unimaginative and badly animated straight-to-video sequels have been churned out. It feels kind of like something’s been festering under the surface for some time, and the boil has just burst. National Princess Week is just the end result. It makes me very sad.

I was not expecting much when I opened this article – then I scrolled down and saw my childhood library staring at me. The Enchanted Forest Chronicles are probably the first book series I truly loved, followed by Tamora Pierce’s Tortall books a few years later (and not just Alanna! Daine, and Kel, and Aly, and Beka as well – I read Alanna: the First Adventure at about 11, and am still reading today at 22). Thank you, thank you for this.

Would also recommend “The Ordinary Princess,” by M.M. Kaye – I read it long ago, but still have fond memories.

I really liked this post. I loved all those books when I was younger and this makes me want to re-read them all again!

I loved “Dealing with Dragons” and that whole trilogy in middle school. Even after I forgot the name of the book I remembered “the one with the princess who lived with a dragon.” I’m thrilled this book and the others are being brought up again in defense against America’s Disney saturated, hyper-girly princess obsession.

[…] from Bailey Shoemaker Richards, because she wrote it better than I would on her blog post about Princess Week on SPARK (Sexualization, Protest, Action Resistance, Knowledge), the princess concept marketed by […]