by Anya Josephs

Thanks to SPARK’s generous friends at the Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media, I was able to join SPARK Executive Director Dana Edell and Program Coordinator Melissa Campbell at the 2nd Global Symposium on Gender in the Media. This afternoon-long conversation featured speeches by Geena Davis and Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, the Executive-Director of UN Women, as well as panels on global storytelling and the impact the media can have on issues concerning girls. However, the centerpiece of the afternoon was really the presentation by Dr. Stacy L. Smith of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, on the research she and her team have done, “Gender Bias Without Borders.”

and Program Coordinator Melissa Campbell at the 2nd Global Symposium on Gender in the Media. This afternoon-long conversation featured speeches by Geena Davis and Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, the Executive-Director of UN Women, as well as panels on global storytelling and the impact the media can have on issues concerning girls. However, the centerpiece of the afternoon was really the presentation by Dr. Stacy L. Smith of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, on the research she and her team have done, “Gender Bias Without Borders.”

This work is so incredibly vital. Smith and her team have worked hard to come up with solid statistics that prove just how wide the gender gap of representation in films and television is. A lot of the work we do here at SPARK is on that subject, but we often talk about specific films or television shows, whether we’re praising or critiquing them. In other words, we have anecdotes—individual examples, considered in isolation. Smith’s work allows us to see a broader picture of the status of women and girls in the media—and the picture is very grim indeed.

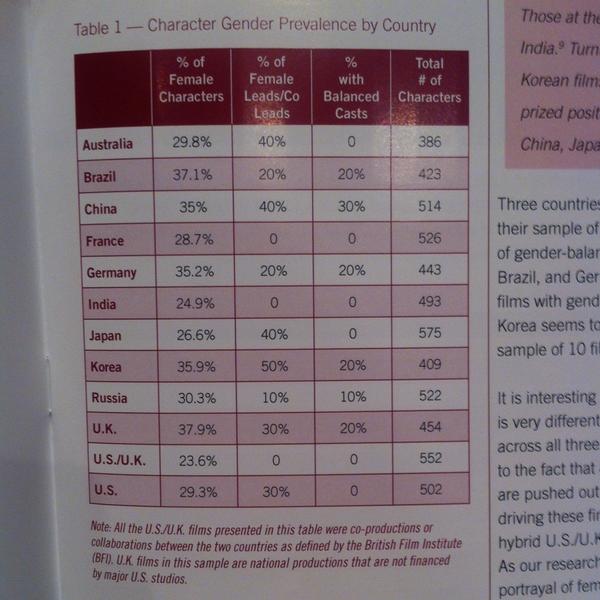

In the 120 films and 5,799 speaking roles surveyed, 31% of speaking roles belong to women, and a mere 23% of protagonists are women. Only 10% of films in the sample have an equal number of girls and boys in the cast. Women onscreen are almost all sexualized. The women that do appear are rarely in positions of leadership—for instance, of the thousands of characters studied, there were only 11 female CEOs, and two of those 11 were Marvel character Pepper Potts (who was gifted her fictional corporation by her boyfriend). There are almost no fields were men and women have parity in representation. This is the first global study of its kind, and Smith’s research shows that it isn’t just a problem of US media. All around the world, girls and women are being mis- and underrepresented in media. However, it also a uniquely American responsibility, since so much media (up to 80% of films worldwide) is created in the U.S.

This isn’t just a question of the media. The Institute’s motto is “if she can see it, she can be it”—they argue that girls need many possibilities for their lives represented in the media. They point to the fact that the proportion of women in crowd scenes in movies—17%– is the same as the proportion of women in many arenas of the real world, from Fortune 500 boardrooms to tenured professorships. Their suggestion is that we get so used to not seeing women in the media that we don’t notice that we’re not seeing them in the real world either. Media creates the expectation that girls and women are sexualized, disempowered, or just plain not there—and that makes people complacent when women are sexualized, disempowered, and invisible in the real world as well.

This isn’t just a question of the media. The Institute’s motto is “if she can see it, she can be it”—they argue that girls need many possibilities for their lives represented in the media. They point to the fact that the proportion of women in crowd scenes in movies—17%– is the same as the proportion of women in many arenas of the real world, from Fortune 500 boardrooms to tenured professorships. Their suggestion is that we get so used to not seeing women in the media that we don’t notice that we’re not seeing them in the real world either. Media creates the expectation that girls and women are sexualized, disempowered, or just plain not there—and that makes people complacent when women are sexualized, disempowered, and invisible in the real world as well.

The problem is huge, and progress is slow. In her keynote, Ms. Davis mentioned that at the current rate of improvement, women will have equal representation in the media in a mere seven hundred years. However, it isn’t all bad news.

At the conference, Ms. Davis described the responses she’d gotten from content creators—directors, producers, and screenwriters—she presented this data to. She didn’t get apathy or disinterest. Instead, most of the people who saw this information hadn’t recognized the problem and were deeply concerned to realize they were perpetuating this problem. She even said that many have already made changes based on her report.

The symposium was an event that reinforced the best and worst things about women’s representation in the media. It clarified—and proved rigorously—just how far we have to go, and how slow progress has been. Yet it also emphasized the hard work people everywhere are doing to overcome these problems. With the dedication and commitment of organizers, activists, and researchers, there is hope to show the next generation of girls and boys a brighter image of what they can be.