by Brenda Guesnet

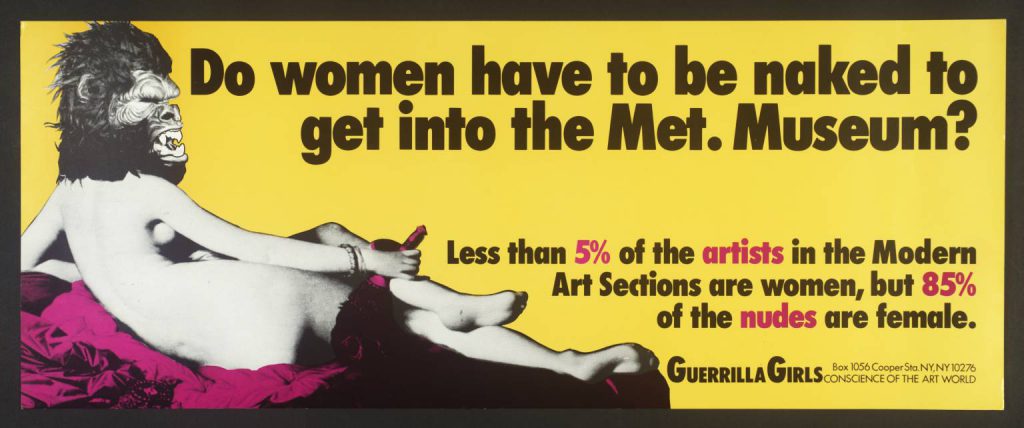

Some of you might be familiar with the image above: it’s arguably the most famous poster artwork of the anonymous feminist group “Guerilla Girls.” The Guerilla Girls have been active since the 1980s, and became famous for their billboards and posters calling out sexism and racism within the art world. The poster does a great job of not only highlighting the fact that women artists have been actively excluded from the “canon” of art, but also connecting this lack directly to the way women have been exploited as – often naked – subjects in art. What this means is that girls and women that visit art museums will see themselves depicted through the male artist’s gaze, rather than as protagonists or the makers of the images they see – art thereby predictably reproduces a pattern we can observe throughout most of society.

What somehow makes this even more dangerous, is that the art context gives this particular brand of sexualization a kind of prestige: as opposed to advertisements or pop music videos, the distinguished halls of an art museum or the pages of a thick textbook lend the images we see there an often unquestioned authority. We forget that there is a conscious – and potentially biased – decision behind every artwork and artist represented, which in turn can make these images even harder to question and reject. Furthermore, art being *art*, people often prefer to see it as something separate from society and politics, rather than holding themselves accountable for oppressions that art perpetuates and reproduces. So that’s exactly what the Guerilla Girls set out to fight against, perhaps ironically eventually entering the exact institutions they were critiquing.

This exclusion of women and people of color from the art world is also what this new ongoing series, SPARK Artists, is all about. What does it mean to be a woman or girl artist working within such a patriarchal tradition? How does it affect women artists’ work, if at all, and how do they perhaps attempt to fight back against this through their art? Should we even be approaching women artist’s work through the lens of gender and feminism, or is this actually counterproductive and limiting? This series will be exploring these questions through both real live women and girl artists and those that chose this profession perhaps under even more difficult conditions a couple of decades (or centuries) ago.

Despite their institutionalization, the Guerilla Girls are pretty revolutionary in a lot of ways, and the fact that they rose to such fame can, in my opinion, only have worked towards a more equal acknowledgement of female artists. The group formed in 1985 when the MOMA staged an exhibition that was framed as being a definitive survey of contemporary art – but featured only 13 female artists out of 169. The soon-to-be Guerilla Girls were outraged, for obvious reasons, and as their protest garnered little attention, they decided to form an anonymous collective, trademarked by intimidating gorilla masks. Up to this day, no one knows who is behind these masks, because the members refuse to show their faces and adopt pseudonyms of dead female artists such as Frida Kahlo or Käthe Kollwitz. To take such an approach within a Western art context that is very intent on individual authorship (never mind that the most expensive works nowadays are made by artist’s assistants) and fosters an obsession over big names and personalities, is pretty radical.

Thinking about how to make a change in the sexism of the art world, the Guerilla Girls’ emphasis on the collective in opposition to the idea of the individual genius is crucial: we can’t just replace our old geniuses with new ones, and merely revising art history books to “uncover” women artists and artists of color won’t do either. Instead, we have to question the very notions of a canon and of individual genius that have produced this patriarchal structure, in order to overthrow it.

individual genius is crucial: we can’t just replace our old geniuses with new ones, and merely revising art history books to “uncover” women artists and artists of color won’t do either. Instead, we have to question the very notions of a canon and of individual genius that have produced this patriarchal structure, in order to overthrow it.

The “anonymous collective” concept isn’t the only thing we can learn from the Guerilla Girls: the fact that they are basically a grassroots movement means that they can still inspire many ways in which we can protest the ongoing exclusion of women from and the sexualization of women in art. For instance, the Guerilla Girls used to do “weenie counts” in museums (counting the amount of male artists as opposed to female ones, or the amount of naked women as opposed to men) – why not do this in your local museum to find out how well women are represented there? They also put hundreds of stickers in and around museums to protest their female to male ratios. And one thing that has definitely changed since the 1980’s is museums’ presence on social media: this gives us another great platform to call institutions out on their sexism and lack of representation.

A couple of things may have changed since the first Guerilla Girls poster was released in 1989, but women artists and artists of color remain highly underrepresented in the art world. This is why SPARK is launching a new series – SPARK Artists – that highlights female visual artists and their work. We will be writing about and interviewing artists across all mediums, continents, backgrounds, and eras, including both artists that have “made it” as well as those just starting out. Following SPARK’s mission to end sexualization, this series is motivated by the belief that supporting and promoting female artists and artists of color is vital for the fight against sexualization – both in art and beyond.